Die Mauer

The early days of the Berlin Wall.

By John Bainbridge

The wall that divides Berlin is hard to visualize, because it defies comparison. Other things in the city are easy enough to imagine, because they can be Iikened to something familiar—the Kurfürstendamm to Fifth Avenue, Potsdamer Platz (in an earlier period) to Times Square, the Spree River to the East River, and so on. But there has been never been anything quite like die Mauer—or, as Mayor Willy Brandt has called it, die Schandmauer (the wall of shame). Its purpose alone would make it unique. Countries have built walls to keep their enemies out; die Mauer is probably the only wall ever built to keep a people in.

Physically, too, it is in a class by itself. Unlike the Great Wall of China, Hadrian’s Wall, and other walls that have figured in history, it is an engineering and architectural laughingstock. It isn’t even very long, as famous Walls go. The Great Wall stretched for fifteen hundred miles, Hadrian’s for almost seventy-five. Die Mauer is only twenty-seven miles over all. It runs along the sector border—the line that was drawn approximately through the center of Greater Berlin in 1945 by the Four Powers to mark off the Soviet and Allied occupation areas—and since the sector border, which follows some of Berlin’s old borough borders, is even more eccentric than most territorial boundaries, the wall runs a highly irregular course, going for a certain distance in one direction, veering off in another, curving slightly here, making a ninety-degree turn there, cutting through parks, squares, cemeteries, factory lots, and waterways, and continuing thus on its ragged way. It is anything but uniform in construction. In outlying sections of the city, it consists mainly of two ten-foot-high barbed-wire fences spaced about six feet apart. Along several streets, it is a row of vacant apartment houses whose doors and windows have been bricked shut. For a few blocks, it incorporates a red brick wall bounding one side of a cemetery, and for more than a mile the Spree serves as the wall. For the most part, though, it is made of materials originally intended for housing construction—a circumstance that contributes to its generally implausible appearance. At the base of the wall, there is usually a row of upright prefabricated concrete slabs about four and a half feet square and a foot thick. These were not set into excavated foundations but merely laid on the ground. As a result, when the ground heaved during last spring’s thaws the wall fell down in a few places, and East German workers had to put it up again. On top of the slabs there may be a couple of rows of regulation-size concrete building blocks and, above them, a piece of smoothly finished concrete about thirty inches long and twelve inches square. All these blocks and slabs are held together with mortar that drips messily down the sides. Surmounting the structure at intervals of about three feet are Y-shaped pieces of metal, on which are strung strands of barbed wire that have become rusty. These are the usual components, but they are not always assembled in the same way. Sometimes, the master builders slapped a second piece of finished concrete on top of the first. Other times, they didn’t. Occasionally, they put up a stretch using building blocks exclusively. Not surprisingly, the wall varies a good deal in height. As a rule, it is about ten feet high, but in some places it is twice that, and it may vary by a couple of feet as many as three or four times in the course of a city block. There is, however, one consistent thing about the wall, and that is shoddy workmanship. It looks, as a Berlin sculptor has remarked, as if it had been thrown together by a band of backward apprentice stonemasons when drunk.

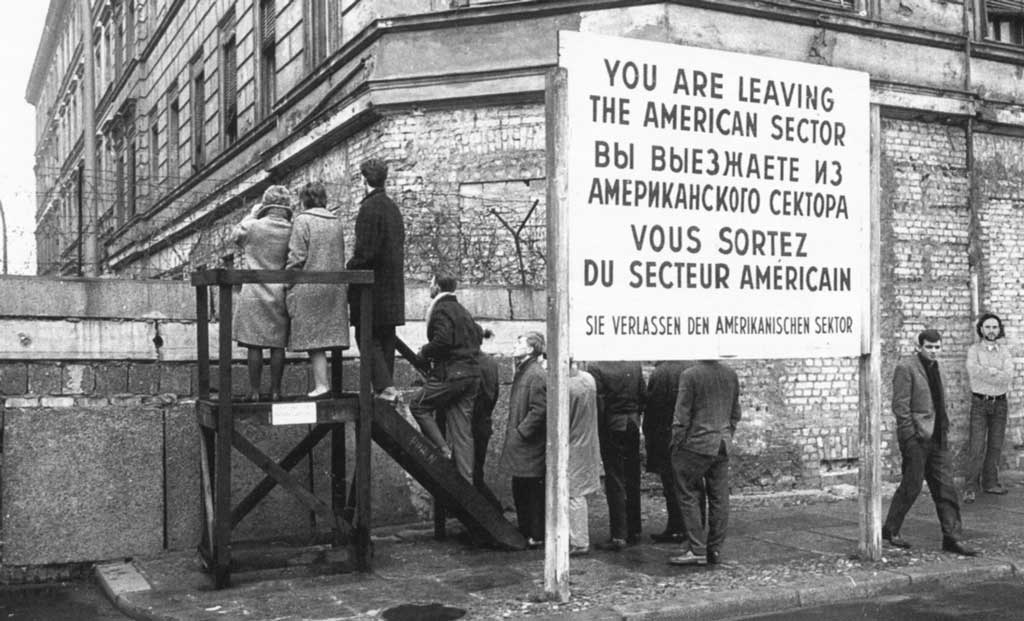

No matter how unprepossessing it is, the wall has largely realized its main immediate objective—the elimination of West Berlin as an escape hatch for residents of East Germany. From 1945 until August 13, 1961, when the wall went up, nearly four million citizens of East Germany—roughly, one out of every four—fled to the West. As a result, East Germany earned the distinction of being the only country in Europe, if not in the world, that had both an excess of births over deaths and a steadily declining population. The mass emigration was not only politically embarrassing but economically crippling. For the first few years following the Second World War, exact records were not kept of the numbers and occupations of the refugees. After the early nineteen-fifties, however, sixty-one per cent of those who fled had been gainfully employed. Among the émigrés were a hundred and fifty thousand farmers and farm workers; forty-seven hundred doctors and dentists; eight hundred judges, lawyers, notaries, and state attorneys; more than seventeen thousand teachers; and an almost equal number of engineers and technicians. About half of all the refugees were under the age of twenty-five; thirty thousand were students. Though East Germany could ill afford to lose any of its people (its population is now seventeen million, and that of West Germany fifty-three million), it was the exodus of young workers that was of most concern to the regime and its leader, Walter Ulbricht. As he complained in Pravda last year, “It cost us more than thirty billion marks [about $1,500,000,000] just to prepare a labor force, which was then recruited by West Germany.” Two weeks before the wall went up, he told a reporter from the London Evening Standard, “This is no political emigration but filthy man-trade, which is carried out with large sums of money invested by Bonn authorities, West Germany monopoly capital, and the United States spy centers in West Berlin.” Ulbricht and his colleagues also described the mass departure as “filthy head-hunting” and “filthy slave trading,” and they did what they could to stop it. One step was to pass a law in 1956 making Republikflucht (fleeing the republic) a crime punishable by three years’ imprisonment. (The Constitution of the German Democratic Republic guarantees the freedom to emigrate, which it calls “one of the truly basic freedoms.” However, like so many other Communist guarantees, this one contains a joker, for the Constitution also says that the right to emigrate can be restricted by law.) As another step, East Germany established elaborate security measures three miles in depth along its eight-hundred-and-sixty-mile border with West Germany. Yet as long as the escape route through Berlin remained open, the flow of refugees could not be staunched. It was not difficult for an East German to travel to East Berlin, and, once there, he needed only to buy a ticket on the U-Bahn (subway) or S-Bahn (elevated) and ride to West Berlin. Some refugees walked across the border; others took a taxi. All of them ran the risk of encountering spot customs checks by the East German border guards. From time to time, the Vopos—an abbreviation for the Volkspolizei, or People’s Police, and now, by extension, the usual term for all East German armed forces on border duty—arrested intended refugees who had given themselves away by nervous behavior or suspicious luggage, or had been denounced by informers. However, the great majority of refugees from East Germany used the Berlin route successfully. It was open to almost anyone who was ready to leave behind him, among other things, his job, his home, and his personal possessions.

No matter how unprepossessing it is, the wall has largely realized its main immediate objective—the elimination of West Berlin as an escape hatch for residents of East Germany. From 1945 until August 13, 1961, when the wall went up, nearly four million citizens of East Germany—roughly, one out of every four—fled to the West. As a result, East Germany earned the distinction of being the only country in Europe, if not in the world, that had both an excess of births over deaths and a steadily declining population. The mass emigration was not only politically embarrassing but economically crippling. For the first few years following the Second World War, exact records were not kept of the numbers and occupations of the refugees. After the early nineteen-fifties, however, sixty-one per cent of those who fled had been gainfully employed. Among the émigrés were a hundred and fifty thousand farmers and farm workers; forty-seven hundred doctors and dentists; eight hundred judges, lawyers, notaries, and state attorneys; more than seventeen thousand teachers; and an almost equal number of engineers and technicians. About half of all the refugees were under the age of twenty-five; thirty thousand were students. Though East Germany could ill afford to lose any of its people (its population is now seventeen million, and that of West Germany fifty-three million), it was the exodus of young workers that was of most concern to the regime and its leader, Walter Ulbricht. As he complained in Pravda last year, “It cost us more than thirty billion marks [about $1,500,000,000] just to prepare a labor force, which was then recruited by West Germany.” Two weeks before the wall went up, he told a reporter from the London Evening Standard, “This is no political emigration but filthy man-trade, which is carried out with large sums of money invested by Bonn authorities, West Germany monopoly capital, and the United States spy centers in West Berlin.” Ulbricht and his colleagues also described the mass departure as “filthy head-hunting” and “filthy slave trading,” and they did what they could to stop it. One step was to pass a law in 1956 making Republikflucht (fleeing the republic) a crime punishable by three years’ imprisonment. (The Constitution of the German Democratic Republic guarantees the freedom to emigrate, which it calls “one of the truly basic freedoms.” However, like so many other Communist guarantees, this one contains a joker, for the Constitution also says that the right to emigrate can be restricted by law.) As another step, East Germany established elaborate security measures three miles in depth along its eight-hundred-and-sixty-mile border with West Germany. Yet as long as the escape route through Berlin remained open, the flow of refugees could not be staunched. It was not difficult for an East German to travel to East Berlin, and, once there, he needed only to buy a ticket on the U-Bahn (subway) or S-Bahn (elevated) and ride to West Berlin. Some refugees walked across the border; others took a taxi. All of them ran the risk of encountering spot customs checks by the East German border guards. From time to time, the Vopos—an abbreviation for the Volkspolizei, or People’s Police, and now, by extension, the usual term for all East German armed forces on border duty—arrested intended refugees who had given themselves away by nervous behavior or suspicious luggage, or had been denounced by informers. However, the great majority of refugees from East Germany used the Berlin route successfully. It was open to almost anyone who was ready to leave behind him, among other things, his job, his home, and his personal possessions.

The number of East Germans willing to accept these terms in order to get out of the country averaged about nineteen thousand a month from 1950 through the first half of 1961. In July of that year, 30,415 people crossed over. And in the first days of August, the stream of refugees reached flood proportions. The deluge was partly a response to the discouraging outcome of the Kennedy-Khrushchev meeting in Vienna in June, and partly a response to events within East Germany, such as a rise in the work quotas, a speedup of the collectivization of agriculture, and an intensified campaign of harassment of the “boundary walkers”—some sixty thousand people who lived in East Berlin and worked in West Berlin. Thanks to hindsight, it is not difficult now to see that some measure to stop the drain of manpower—perhaps the erection of a wall—was imminent. In fact, Ulbricht had suggested as much, though only in the customary reversible Communist terms. In mid-June, he had said flatly at a press conference, “Nobody has the intention of building a wall.” More clues turned up in July. The East German newspapers approached hysteria in their agitation against “slave trading.” More and more “boundary walkers” were stopped at the border or required to surrender their identity cards. By the beginning of August, the East German border police had been reinforced to six times their former strength. It was estimated that in the week between July 29th and August 4th every second Berlin-bound refugee was intercepted. Nevertheless, 10,419 refugees—a record number—got through. As the next week began, West Berlin newspapers reported that Ulbricht was in Moscow and that he had asked Khrushchev to permit the blocking of the border forthwith. A few days later, the newspapers announced that Khrushchev had sent his secret-police chief to East Berlin. At this time, too, the East German press was printing a great many letters from individual citizens and resolutions from groups demanding the immediate closing of the border; this was a telltale sign, for a similar spate of “spontaneous” communications had preceded every coercive measure undertaken in East Germany. All these portents contributed to the building up of a now-or-never mood among East Germans who had considered fleeing, and they left by the thousands. They swamped Marienfelde, the refugee reception center in West Berlin. The British Army set up tents around the center to shelter the multitudes waiting to be admitted; the American Army supplied as many as twenty-five hundred field rations a day to help feed them; and Pan American, Air France, and British European Airways—the three airlines that are permitted to provide service to West Berlin—flew about a thousand refugees a day to camps in West Germany. On August 11th, the West Berlin newspapers said quite specifically that the East German authorities had met that morning and had probably reached a decision to close the border. On that day and the next, thousands of refugees made their way to West Berlin, bringing the total for the first twelve days of August to more than forty-five thousand.

The number of East Germans willing to accept these terms in order to get out of the country averaged about nineteen thousand a month from 1950 through the first half of 1961. In July of that year, 30,415 people crossed over. And in the first days of August, the stream of refugees reached flood proportions. The deluge was partly a response to the discouraging outcome of the Kennedy-Khrushchev meeting in Vienna in June, and partly a response to events within East Germany, such as a rise in the work quotas, a speedup of the collectivization of agriculture, and an intensified campaign of harassment of the “boundary walkers”—some sixty thousand people who lived in East Berlin and worked in West Berlin. Thanks to hindsight, it is not difficult now to see that some measure to stop the drain of manpower—perhaps the erection of a wall—was imminent. In fact, Ulbricht had suggested as much, though only in the customary reversible Communist terms. In mid-June, he had said flatly at a press conference, “Nobody has the intention of building a wall.” More clues turned up in July. The East German newspapers approached hysteria in their agitation against “slave trading.” More and more “boundary walkers” were stopped at the border or required to surrender their identity cards. By the beginning of August, the East German border police had been reinforced to six times their former strength. It was estimated that in the week between July 29th and August 4th every second Berlin-bound refugee was intercepted. Nevertheless, 10,419 refugees—a record number—got through. As the next week began, West Berlin newspapers reported that Ulbricht was in Moscow and that he had asked Khrushchev to permit the blocking of the border forthwith. A few days later, the newspapers announced that Khrushchev had sent his secret-police chief to East Berlin. At this time, too, the East German press was printing a great many letters from individual citizens and resolutions from groups demanding the immediate closing of the border; this was a telltale sign, for a similar spate of “spontaneous” communications had preceded every coercive measure undertaken in East Germany. All these portents contributed to the building up of a now-or-never mood among East Germans who had considered fleeing, and they left by the thousands. They swamped Marienfelde, the refugee reception center in West Berlin. The British Army set up tents around the center to shelter the multitudes waiting to be admitted; the American Army supplied as many as twenty-five hundred field rations a day to help feed them; and Pan American, Air France, and British European Airways—the three airlines that are permitted to provide service to West Berlin—flew about a thousand refugees a day to camps in West Germany. On August 11th, the West Berlin newspapers said quite specifically that the East German authorities had met that morning and had probably reached a decision to close the border. On that day and the next, thousands of refugees made their way to West Berlin, bringing the total for the first twelve days of August to more than forty-five thousand.

Shortly before two o’clock the next morning—a Sunday—East German armed forces began sealing off the sector border. The undertaking was handled as if it were a military operation of high risk. Under cover of darkness, some forty thousand heavily armed soldiers and police, supported by tanks, armored cars, personnel carriers, trucks equipped with water cannon, and other military vehicles, took up positions along the border. By dawn, the troops had strung up thousands of feet of barbed wire; felled trees across streets; cut streetcar tracks and turned the ends up to make crude bumpers; and torn up paving stones and dug trenches across avenues and squares. East Berlin took on the aspect of a besieged city. Until August 13th, it had been possible to cross the border at the Brandenburg Gate and at eighty other points, as well as on the subway and elevated. Now the Brandenburg Gate was closed, and so were all but twelve of the other crossing points. (These were later reduced to seven.) That same day, the East German authorities stopped direct subway and elevated travel between the two parts of the city and issued a decree forbidding any inhabitant of East Germany or East Berlin to set foot in West Berlin. A subsequent decree had the effect of barring West Berliners from crossing into East Berlin. West Germans and foreigners are still allowed to visit East Berlin, and so, of course, are Allied personnel.

Shortly before two o’clock the next morning—a Sunday—East German armed forces began sealing off the sector border. The undertaking was handled as if it were a military operation of high risk. Under cover of darkness, some forty thousand heavily armed soldiers and police, supported by tanks, armored cars, personnel carriers, trucks equipped with water cannon, and other military vehicles, took up positions along the border. By dawn, the troops had strung up thousands of feet of barbed wire; felled trees across streets; cut streetcar tracks and turned the ends up to make crude bumpers; and torn up paving stones and dug trenches across avenues and squares. East Berlin took on the aspect of a besieged city. Until August 13th, it had been possible to cross the border at the Brandenburg Gate and at eighty other points, as well as on the subway and elevated. Now the Brandenburg Gate was closed, and so were all but twelve of the other crossing points. (These were later reduced to seven.) That same day, the East German authorities stopped direct subway and elevated travel between the two parts of the city and issued a decree forbidding any inhabitant of East Germany or East Berlin to set foot in West Berlin. A subsequent decree had the effect of barring West Berliners from crossing into East Berlin. West Germans and foreigners are still allowed to visit East Berlin, and so, of course, are Allied personnel.

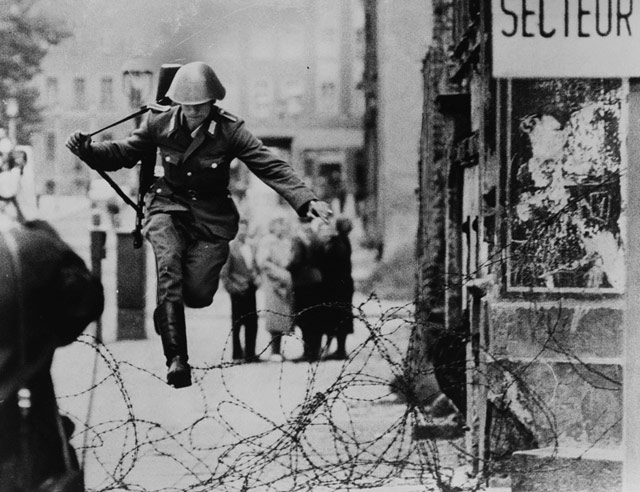

At first, considerable portions of the wall consisted of nothing more than knee-high coils of barbed wire or shoulder-high fencing nailed to wooden poles. For a few days, dozens of East Germans found their way around or through these obstacles without great difficulty. Many others made it by swimming across the Spree or some other waterway. In those days, the East German border guards were neither as alert nor as ruthless as they have since become, and East Berliners could talk through the improvised barrier to relatives and friends, and even exchange parcels with them. Once the East German authorities realized that their coup had succeeded, however, they lost no time in stiffening the flimsy barricade with concrete. In addition, they not only ordered East Berliners not to go near the wall but insolently warned West Berliners against approaching within a hundred metres of it, “in the interests of their own safety.” To try to make this stick, the Vopos started firing warning shots whenever small groups of West Berliners congregated near the wall. The Western commandants thereupon dispatched troops in battle dress to the sector boundary, and kept them there until the East Germans stopped trying to enforce that injunction. By then—about a month after the border was sealed off—East Berliners had been forbidden to wave in the direction of the wall, even if they were blocks away from it. (As recently as this July, eight East Berliners were taken into custody during one day for waving.) At former crossing points, where large numbers of West Berliners hopefully continued to gather, the East Germans erected high wooden screens, completely blocking the view into the “workers’ paradise.”

At first, considerable portions of the wall consisted of nothing more than knee-high coils of barbed wire or shoulder-high fencing nailed to wooden poles. For a few days, dozens of East Germans found their way around or through these obstacles without great difficulty. Many others made it by swimming across the Spree or some other waterway. In those days, the East German border guards were neither as alert nor as ruthless as they have since become, and East Berliners could talk through the improvised barrier to relatives and friends, and even exchange parcels with them. Once the East German authorities realized that their coup had succeeded, however, they lost no time in stiffening the flimsy barricade with concrete. In addition, they not only ordered East Berliners not to go near the wall but insolently warned West Berliners against approaching within a hundred metres of it, “in the interests of their own safety.” To try to make this stick, the Vopos started firing warning shots whenever small groups of West Berliners congregated near the wall. The Western commandants thereupon dispatched troops in battle dress to the sector boundary, and kept them there until the East Germans stopped trying to enforce that injunction. By then—about a month after the border was sealed off—East Berliners had been forbidden to wave in the direction of the wall, even if they were blocks away from it. (As recently as this July, eight East Berliners were taken into custody during one day for waving.) At former crossing points, where large numbers of West Berliners hopefully continued to gather, the East Germans erected high wooden screens, completely blocking the view into the “workers’ paradise.”

On August 13th, the East Germans also began a systematic evacuation of dwellings situated on or near the border. Private houses were demolished to make way for a so-called “death strip,” or no man’s land. Searchlights were installed to illuminate the death strip at night. Hundreds of East Berliners owned small plots of land along the border, where they had cultivated gardens and, in many cases, had built small cottages of some kind for use on weekends. The garden areas, too, were levelled and bulldozed by Vopos, who were sometimes urged on by Communist fighting songs issuing from a sound truck. The apartment houses on the border presented a more difficult problem. In several places—on Bernauerstrasse, for example—the buildings on the east side of the street are in East Berlin, and the sidewalks and the street in West Berlin. Since this meant that a resident could walk out his front door to freedom, the East Germans started, on August 13th, to wall up the entrances to all those buildings. Residents immediately began leaving by way of first-floor windows, after throwing a few possessions into the street. The windows on the first and second floors were then bricked up, after which refugees departed from third-floor windows by lowering themselves on ropes or jumping into rescue nets held by members of the West Berlin Fire Brigade. As the bricking up of the windows proceeded, the attempts to escape by jumping continued, though they were fewer and some ended in death. The Vopos thwarted as many as they could by throwing tear-gas bombs at the firemen holding rescue nets. Frequently, too, they sent out false alarms. They would arrange for a decoy to appear at an apartment window and signal his wish to jump. A West Berlin policeman or someone else on the street would summon the fire brigade, and when the firemen had arrived and were holding the net, the Vopos would shower them with stones and red paint. Meanwhile, the authorities were evacuating the apartment houses—first floor by floor and then entire buildings at one time. A typical operation of this kind got under way shortly before dawn one day in mid-October of 1961, when detachments of Vopos and other military units, a fleet of moving vans, and about a hundred civilians wearing armbands to show that they were functionaries of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or S.E.D.—the Communist Party—descended on Harzerstrasse. The functionaries went through a row of apartment buildings and told the two hundred and fifty families living in them to start packing; van after van drove off to an undisclosed destination and returned to be filled again. The evacuation went on uninterruptedly for two days and three nights. Then the buildings were empty, and the evacuation team moved on.

On August 13th, the East Germans also began a systematic evacuation of dwellings situated on or near the border. Private houses were demolished to make way for a so-called “death strip,” or no man’s land. Searchlights were installed to illuminate the death strip at night. Hundreds of East Berliners owned small plots of land along the border, where they had cultivated gardens and, in many cases, had built small cottages of some kind for use on weekends. The garden areas, too, were levelled and bulldozed by Vopos, who were sometimes urged on by Communist fighting songs issuing from a sound truck. The apartment houses on the border presented a more difficult problem. In several places—on Bernauerstrasse, for example—the buildings on the east side of the street are in East Berlin, and the sidewalks and the street in West Berlin. Since this meant that a resident could walk out his front door to freedom, the East Germans started, on August 13th, to wall up the entrances to all those buildings. Residents immediately began leaving by way of first-floor windows, after throwing a few possessions into the street. The windows on the first and second floors were then bricked up, after which refugees departed from third-floor windows by lowering themselves on ropes or jumping into rescue nets held by members of the West Berlin Fire Brigade. As the bricking up of the windows proceeded, the attempts to escape by jumping continued, though they were fewer and some ended in death. The Vopos thwarted as many as they could by throwing tear-gas bombs at the firemen holding rescue nets. Frequently, too, they sent out false alarms. They would arrange for a decoy to appear at an apartment window and signal his wish to jump. A West Berlin policeman or someone else on the street would summon the fire brigade, and when the firemen had arrived and were holding the net, the Vopos would shower them with stones and red paint. Meanwhile, the authorities were evacuating the apartment houses—first floor by floor and then entire buildings at one time. A typical operation of this kind got under way shortly before dawn one day in mid-October of 1961, when detachments of Vopos and other military units, a fleet of moving vans, and about a hundred civilians wearing armbands to show that they were functionaries of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or S.E.D.—the Communist Party—descended on Harzerstrasse. The functionaries went through a row of apartment buildings and told the two hundred and fifty families living in them to start packing; van after van drove off to an undisclosed destination and returned to be filled again. The evacuation went on uninterruptedly for two days and three nights. Then the buildings were empty, and the evacuation team moved on.

On a recent visit to Berlin, I saw what a street that has been made part of the wall looks like; one afternoon I walked the length of Bernauerstrasse—a distance of about a mile—in the company of a Berlin newspaper editor. We stayed on the west side of the street, at the suggestion of a policeman, who said that Vopos patrolling the vacated buildings liked to drop things on people venturing along the east side. A walk down Bernauerstrasse is a sickening experience. While people go in and out of the shops and apartment houses on the west side of the street, the other side is empty and silent. From one end to the other, no living thing appears. My companion said that the buildings had been taken over by rats. The dead buildings, stretched out in a long line, show the signs of violence committed on them in every door and window, crudely sealed with bricks of various sizes, shapes, and colors (some red, some white, some yellow)—often mixed together. As a rule, the window frames were knocked out and the entire aperture bricked up. In a few places, both the frames and the windows were left, and the opening was sealed from the inside; one looks through dirty panes of glass at a sloppy blank wall of bricks—a sight all the more repugnant when, as occurs here and there, remnants of curtains are still hanging at the window. On the roofs, barbed wire is strung along the front edges and from chimney to chimney. The spaces between the buildings have been filled in with the familiar concrete slabs and blocks and topped with barbed wire. Looking closely at the upper stories, one can see places where a few bricks have been removed to provide lookouts for the Vopos. Otherwise, there is nothing but a solid façade of ugly, ashen masonry. As we neared the end of this spectral thoroughfare, my companion said, “We call this Berlin’s first completely socialized street.”

On a recent visit to Berlin, I saw what a street that has been made part of the wall looks like; one afternoon I walked the length of Bernauerstrasse—a distance of about a mile—in the company of a Berlin newspaper editor. We stayed on the west side of the street, at the suggestion of a policeman, who said that Vopos patrolling the vacated buildings liked to drop things on people venturing along the east side. A walk down Bernauerstrasse is a sickening experience. While people go in and out of the shops and apartment houses on the west side of the street, the other side is empty and silent. From one end to the other, no living thing appears. My companion said that the buildings had been taken over by rats. The dead buildings, stretched out in a long line, show the signs of violence committed on them in every door and window, crudely sealed with bricks of various sizes, shapes, and colors (some red, some white, some yellow)—often mixed together. As a rule, the window frames were knocked out and the entire aperture bricked up. In a few places, both the frames and the windows were left, and the opening was sealed from the inside; one looks through dirty panes of glass at a sloppy blank wall of bricks—a sight all the more repugnant when, as occurs here and there, remnants of curtains are still hanging at the window. On the roofs, barbed wire is strung along the front edges and from chimney to chimney. The spaces between the buildings have been filled in with the familiar concrete slabs and blocks and topped with barbed wire. Looking closely at the upper stories, one can see places where a few bricks have been removed to provide lookouts for the Vopos. Otherwise, there is nothing but a solid façade of ugly, ashen masonry. As we neared the end of this spectral thoroughfare, my companion said, “We call this Berlin’s first completely socialized street.”

While the Communists were trying to make West Berlin’s front door impenetrable by strengthening the wall, they were also making it more difficult to get through the city’s back door by increasing the fortifications along the zonal border. This is West Berlin’s boundary on the west, north, and south—a zigzag line, sixty-nine miles long, separating the city from East Germany. Though the zonal border is more than twice the length of the sector border, it has been the scene of comparatively few escapes. It is not hard to understand why after seeing it, as I did one morning, accompanied by an American Army colonel, wearing a sports jacket and slacks, who picked me up at my hotel and drove me out in an Opel sedan. On the way, he told me that he had been stationed in Berlin for five years, and had become fond of both the city and the people. “Of course, since August 13th, you feel a little more hemmed in,” he added. “East Berlin has the most beautiful parks and forests and the largest lakes, and West Berliners by the thousands used to spend their Sundays there. Now, on a nice Sunday, In the Grunewald, which is the largest forest in West Berlin, you have a hard time walking ten feet without stepping on someone. But if you want to get an idea of the really important and rough effects of the wall, just imagine waking up one morning to find Manhattan divided by a wall down the middle of Fifth Avenue from the Battery to the Bronx. You live on West Tenth Street, and your office is on Park Avenue. Well, you’re not going to work there any more. Your parents live on East Eighty-second Street. You’re not going to see them, and you’re not going to the East Side to visit a hospital or see a movie or anything of the kind. And nobody over there is coming to see you.” The colonel said that probably seven out of ten West Berliners have relatives or close friends in East Berlin. Because of the suddenness with which the border was closed, husbands were separated from their wives and parents from their small children. Engaged couples who lived on opposite sides of the border had to give up their marriage plans. West Berliners could no longer attend their church if it was in East Berlin, or visit cemeteries there. The lives of East Berliners have been sorely diminished. Before the wall went up, a quarter of a million of them crossed into West Berlin every day to visit, shop, attend the theatre, concerts, and movies, and use libraries where they could read books and newspapers forbidden at home. “Thousands of East Berliners used to come over, maybe only for an hour or two, just to walk around and feel free in a free city,” the colonel said. “It’s hard to overestimate what that meant to them—and to West Berliners, to the Germans as a whole, and to the West. Certainly it was the most effective answer to the Communist propaganda.

While the Communists were trying to make West Berlin’s front door impenetrable by strengthening the wall, they were also making it more difficult to get through the city’s back door by increasing the fortifications along the zonal border. This is West Berlin’s boundary on the west, north, and south—a zigzag line, sixty-nine miles long, separating the city from East Germany. Though the zonal border is more than twice the length of the sector border, it has been the scene of comparatively few escapes. It is not hard to understand why after seeing it, as I did one morning, accompanied by an American Army colonel, wearing a sports jacket and slacks, who picked me up at my hotel and drove me out in an Opel sedan. On the way, he told me that he had been stationed in Berlin for five years, and had become fond of both the city and the people. “Of course, since August 13th, you feel a little more hemmed in,” he added. “East Berlin has the most beautiful parks and forests and the largest lakes, and West Berliners by the thousands used to spend their Sundays there. Now, on a nice Sunday, In the Grunewald, which is the largest forest in West Berlin, you have a hard time walking ten feet without stepping on someone. But if you want to get an idea of the really important and rough effects of the wall, just imagine waking up one morning to find Manhattan divided by a wall down the middle of Fifth Avenue from the Battery to the Bronx. You live on West Tenth Street, and your office is on Park Avenue. Well, you’re not going to work there any more. Your parents live on East Eighty-second Street. You’re not going to see them, and you’re not going to the East Side to visit a hospital or see a movie or anything of the kind. And nobody over there is coming to see you.” The colonel said that probably seven out of ten West Berliners have relatives or close friends in East Berlin. Because of the suddenness with which the border was closed, husbands were separated from their wives and parents from their small children. Engaged couples who lived on opposite sides of the border had to give up their marriage plans. West Berliners could no longer attend their church if it was in East Berlin, or visit cemeteries there. The lives of East Berliners have been sorely diminished. Before the wall went up, a quarter of a million of them crossed into West Berlin every day to visit, shop, attend the theatre, concerts, and movies, and use libraries where they could read books and newspapers forbidden at home. “Thousands of East Berliners used to come over, maybe only for an hour or two, just to walk around and feel free in a free city,” the colonel said. “It’s hard to overestimate what that meant to them—and to West Berliners, to the Germans as a whole, and to the West. Certainly it was the most effective answer to the Communist propaganda.

As the colonel talked, we were driving on Heerstrasse to the western edge of the city. The landscape gradually became rural. We passed a sizable field of hay which was being harvested by a woman with a long wooden rake, drove through a checkpoint manned by West Berlin police, and parked about twenty feet from the East German border, which was marked by a white line painted across the street. Beyond the city limits, Heerstrasse leads to a highway that goes to Hamburg. Two Hamburg-bound trailer trucks were parked at the curb on the West Berlin side of the white line; their drivers were taking a rest before starting the hundred-and-ten-mile journey through East Germany, during which it is not advisable to stop. Three young men in shirtsleeves were standing nearby, trying to hitch a ride. The colonel and I got out of the car, but even before we had opened our doors, a Vopo standing about thirty feet inside the East German border had trained his binoculars on us. Just beyond the border was a brightly painted metal sign that featured Picasso’s white dove over representations of Berlin, Potsdam, Warsaw, Moscow, and Peking. “Achtung!” the sign commanded. “This is the beginning of the Zone of Peace. From here it reaches over 10,000 kilometres to the Pacific Ocean.” (The geographical non sequitur, the colonel said, stemmed from the fact that signs like this one were produced for use on the East German-West German border.) A few feet inside the Zone of Peace stood a ten-foot-high fence of barbed wire strung thickly on concrete posts. Six feet behind this fence was a similar one, and six feet behind the second was a third. Directly behind the third fence was a ditch about eight feet wide and three feet deep. Behind the ditch was a strip of land, about thirty yards wide, that had been cleared of trees and brush—the death strip. To the north and south, this formidable band of fortifications stretched as far as one could see, across fields that had once been used for farming and truck gardening. Nothing was growing on them now, nor was there any sign of life. “This border looks much the same over its entire length,” the colonel said. “They’ve mined the death strip in a great many places—we know, because we’ve watched them do it—and they’ve also put up watchtowers about every three thousand feet. Between the towers they’re building bunkers out of earth and logs. There are plenty of searchlights, and plenty of Vopos on patrol. Last December, about half a mile from here, they killed a young student who was trying to help a refugee escape. Three months after that, also not far from here, a thirteen-year-old boy cut the barbed-wire fences in the family meadow, and he and his parents and his sister got out safely. It’s a strong border, but it’s not perfect. There are still places where a person could get through if he studied the situation diligently enough.”

As the colonel talked, we were driving on Heerstrasse to the western edge of the city. The landscape gradually became rural. We passed a sizable field of hay which was being harvested by a woman with a long wooden rake, drove through a checkpoint manned by West Berlin police, and parked about twenty feet from the East German border, which was marked by a white line painted across the street. Beyond the city limits, Heerstrasse leads to a highway that goes to Hamburg. Two Hamburg-bound trailer trucks were parked at the curb on the West Berlin side of the white line; their drivers were taking a rest before starting the hundred-and-ten-mile journey through East Germany, during which it is not advisable to stop. Three young men in shirtsleeves were standing nearby, trying to hitch a ride. The colonel and I got out of the car, but even before we had opened our doors, a Vopo standing about thirty feet inside the East German border had trained his binoculars on us. Just beyond the border was a brightly painted metal sign that featured Picasso’s white dove over representations of Berlin, Potsdam, Warsaw, Moscow, and Peking. “Achtung!” the sign commanded. “This is the beginning of the Zone of Peace. From here it reaches over 10,000 kilometres to the Pacific Ocean.” (The geographical non sequitur, the colonel said, stemmed from the fact that signs like this one were produced for use on the East German-West German border.) A few feet inside the Zone of Peace stood a ten-foot-high fence of barbed wire strung thickly on concrete posts. Six feet behind this fence was a similar one, and six feet behind the second was a third. Directly behind the third fence was a ditch about eight feet wide and three feet deep. Behind the ditch was a strip of land, about thirty yards wide, that had been cleared of trees and brush—the death strip. To the north and south, this formidable band of fortifications stretched as far as one could see, across fields that had once been used for farming and truck gardening. Nothing was growing on them now, nor was there any sign of life. “This border looks much the same over its entire length,” the colonel said. “They’ve mined the death strip in a great many places—we know, because we’ve watched them do it—and they’ve also put up watchtowers about every three thousand feet. Between the towers they’re building bunkers out of earth and logs. There are plenty of searchlights, and plenty of Vopos on patrol. Last December, about half a mile from here, they killed a young student who was trying to help a refugee escape. Three months after that, also not far from here, a thirteen-year-old boy cut the barbed-wire fences in the family meadow, and he and his parents and his sister got out safely. It’s a strong border, but it’s not perfect. There are still places where a person could get through if he studied the situation diligently enough.”

It was a pleasant morning, and the colonel suggested that we walk down a cobblestone road that leads off to the right, parallel to the border. The Vopo continued to watch us through his binoculars as we set off. When we had gone the equivalent of a couple of city blocks, a pair of patrolling Vopos (they never go on border duty singly) came into view behind the barbed-wire fence nearest the road. Each had a submachine gun, or machine pistol, as the Germans call it, slung over his shoulder. When we were nearly abreast of them, they stopped. One checked his wristwatch and wrote something in a notebook; the other raised his binoculars. The colonel and I also stopped. Like most Vopos, these two were young—probably nineteen or twenty—and neither cut a very smart figure. Their uniforms seemed a size too big, they were loaded down with gear, which included steel helmets hanging from their belts (they were wearing forage caps), and they presented a lumpy aspect, as if all their pockets were overstuffed. “They don’t look too sharp,” the colonel said, “but everything they’ve got is the best Ulbricht can give them—the best cloth, best leather, best of everything all the way down the line, including food. Those submachine guns were manufactured in Czechoslovakia. They’re first quality, too.” I decided to get a picture of the Vopos, and took a Minox camera from my pocket. The minute I raised the view finder to my eye, both turned their backs. A few feet away was a fruit tree with low branches (one of the very few trees that I saw left standing anywhere near the East German border); the Vopos camouflaged themselves behind the foliage, and as one again raised his binoculars, the other slid his submachine gun from his shoulder. “They’ll stand there as long as we stand here,” the colonel said. “They think it’s some kind of a game. We might as well go on.”

It was a pleasant morning, and the colonel suggested that we walk down a cobblestone road that leads off to the right, parallel to the border. The Vopo continued to watch us through his binoculars as we set off. When we had gone the equivalent of a couple of city blocks, a pair of patrolling Vopos (they never go on border duty singly) came into view behind the barbed-wire fence nearest the road. Each had a submachine gun, or machine pistol, as the Germans call it, slung over his shoulder. When we were nearly abreast of them, they stopped. One checked his wristwatch and wrote something in a notebook; the other raised his binoculars. The colonel and I also stopped. Like most Vopos, these two were young—probably nineteen or twenty—and neither cut a very smart figure. Their uniforms seemed a size too big, they were loaded down with gear, which included steel helmets hanging from their belts (they were wearing forage caps), and they presented a lumpy aspect, as if all their pockets were overstuffed. “They don’t look too sharp,” the colonel said, “but everything they’ve got is the best Ulbricht can give them—the best cloth, best leather, best of everything all the way down the line, including food. Those submachine guns were manufactured in Czechoslovakia. They’re first quality, too.” I decided to get a picture of the Vopos, and took a Minox camera from my pocket. The minute I raised the view finder to my eye, both turned their backs. A few feet away was a fruit tree with low branches (one of the very few trees that I saw left standing anywhere near the East German border); the Vopos camouflaged themselves behind the foliage, and as one again raised his binoculars, the other slid his submachine gun from his shoulder. “They’ll stand there as long as we stand here,” the colonel said. “They think it’s some kind of a game. We might as well go on.”

Combination photo showing (L-R) East German border soldiers standing at the borderline at Zimmerstrasse/Charlottenstrasse at the Berlin Wall near the Allied checkpoint Charlie in Berlin March 10, 1990, and a general view of the corner of Zimmerstrasse and Charlottenstrasse near the former Allied checkpoint Charlie in Berlin July 14, 2009. REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch (GERMANY ANNIVERSARY POLITICS CITYSCAPE)

About a quarter of a mile farther down the road, we came to a wooden shack the size of three telephone booths put together, which provides shelter for the two West Berlin policemen on border duty in the area. They were sitting nearby on the grass, listening to a transistor radio; M-2 carbines, manufactured in the United States, lay across their knees. Opposite the police shelter, another garishly painted metal sign could be seen through the barbed-wire fence. This one showed Death in the uniform of a Nazi S.S. officer, standing amid a sea of skulls and skeletons labelled “Stalingrad.” To the right of this figure was a drawing that supposedly represented a West Berlin policeman. The message on the sign was addressed to him. It read, “Turn around! Your enemy is behind you. He lost the last war. Now you are supposed to march and die for him again. Turn around! “ “You see those everywhere up and down the border,” one of the policemen said. “The idea is to try to demoralize us and keep us from doing our duty. Ulbricht must think we haven’t got all our cups in the cuphoard. Nobody has to tell us who the enemy is.”

After we had walked on another quarter of a mile or so, the colonel stopped and told me that it was here that the student had been killed last December. His name was Dieter Wohlfahrt, he was twenty, and he was enrolled in the West Berlin Technical University. He had managed to get his fiancée, a girl named Elke, who was also a university student, out of East Berlin with a faked passport. A few weeks later, Elke’s mother sent word that she, too, wanted to flee. Since it was no longer feasible to arrange escapes with the use of false documents, Dieter impetuously decided to rescue her in a Commando-type operation. He got word to Elke’s mother that she should make her way to a farmhouse, owned by a family with whom Dieter had connections, that then stood just beyond the third barbed-wire fence. According to the plan, she was to be at the side of the house nearest the fence at seven o’clock on the night of Saturday, December 9th. The operation began on schedule. Dieter cut a passage through the first fence and was crawling toward the second when he was sighted and shot by a Vopo. The colonel said that evidently somebody had informed, because several other Vopos were at the scene. They arrested Elke’s mother. A West Berlin police patrol arrived a few minutes after the shooting and turned searchlights on the area, but the policemen were held back by the Vopos, brandishing their submachine guns. Since this part of Berlin is in the British Sector, the British Military Police were summoned; they were also prevented by the Vopos from giving assistance. As a result, Dieter, like later casualties at the wall, died while West Berlin police and Allied soldiers looked on. It was nearly two hours before a truck arrived to remove the body. The farmhouse was levelled the next day. The colonel and I turned around and walked back to the main road, where we were again taken under surveillance by the Vopo at the checkpoint. “I see Junior still has the glasses on us,” the colonel said. He thumbed his nose at the Vopo, and with that we got into the car and headed away from the Zone of Peace.

After we had walked on another quarter of a mile or so, the colonel stopped and told me that it was here that the student had been killed last December. His name was Dieter Wohlfahrt, he was twenty, and he was enrolled in the West Berlin Technical University. He had managed to get his fiancée, a girl named Elke, who was also a university student, out of East Berlin with a faked passport. A few weeks later, Elke’s mother sent word that she, too, wanted to flee. Since it was no longer feasible to arrange escapes with the use of false documents, Dieter impetuously decided to rescue her in a Commando-type operation. He got word to Elke’s mother that she should make her way to a farmhouse, owned by a family with whom Dieter had connections, that then stood just beyond the third barbed-wire fence. According to the plan, she was to be at the side of the house nearest the fence at seven o’clock on the night of Saturday, December 9th. The operation began on schedule. Dieter cut a passage through the first fence and was crawling toward the second when he was sighted and shot by a Vopo. The colonel said that evidently somebody had informed, because several other Vopos were at the scene. They arrested Elke’s mother. A West Berlin police patrol arrived a few minutes after the shooting and turned searchlights on the area, but the policemen were held back by the Vopos, brandishing their submachine guns. Since this part of Berlin is in the British Sector, the British Military Police were summoned; they were also prevented by the Vopos from giving assistance. As a result, Dieter, like later casualties at the wall, died while West Berlin police and Allied soldiers looked on. It was nearly two hours before a truck arrived to remove the body. The farmhouse was levelled the next day. The colonel and I turned around and walked back to the main road, where we were again taken under surveillance by the Vopo at the checkpoint. “I see Junior still has the glasses on us,” the colonel said. He thumbed his nose at the Vopo, and with that we got into the car and headed away from the Zone of Peace.

The colonel’s annoyance interested me, because it indicated that he had still not become accustomed to being watched. The tactic irritated me, too, but I had been in Berlin only a few days, and had thought that in time one would get used to it. My German friends and acquaintances apparently had, and seemed somewhat amused when I showed my displeasure, as I did for the first time a couple of days after arriving in Berlin. I was talking to a West Berlin Polizeimeister, or police captain, in a wooden shack overlooking the wall, and was being watched through binoculars by a Vopo standing on a raised platform about ten feet on the other side. After a while, I borrowed the policeman’s binoculars, and trained them on the Vopo. He put his glasses down, turned his back, lighted a cigarette with studied nonchalance, and didn’t train the binoculars on me again until I started to leave. (I played this childish game a few more times, usually with much the same result, though not if the Vopos were officers; the officers glowered but didn’t turn away.) “It shouldn’t bother you,” the Polizeimeister said with a smile. “You must remember that everything the Vopos do is calculated to intimidate us, or to try to. They want to give us the feeling that we’re being watched and that we’re helpless to do anything about it.” Later that day, he took me out to a suburban neighborhood on the sector border, where the wall consisted mainly of barbed-wire fencing. On the West Berlin side, workmen were noisily constructing a new housing development. The East Berlin side was seemingly deserted. “We’re being watched, of course,” the Polizeimeister said, and pointed to places on the roofs of four houses across the border where several pieces of slate had been removed. “The Vopos made those observation slits, and they’re probably up there in one of those attics now, looking out. For them, it’s like in war. They’re always taking cover, spying from concealed positions. They like to stay out of sight, and then appear suddenly with binoculars fixed on you. If they’re not up in an attic, they may be over there on the ground, behind the hedges. Some of them are pretty clever at hiding themselves. It takes a while to pick them out. Our men on border duty work a shift of two hours on and one hour off. If you’re on too long at a stretch, you don’t see the Vopos.”

The colonel’s annoyance interested me, because it indicated that he had still not become accustomed to being watched. The tactic irritated me, too, but I had been in Berlin only a few days, and had thought that in time one would get used to it. My German friends and acquaintances apparently had, and seemed somewhat amused when I showed my displeasure, as I did for the first time a couple of days after arriving in Berlin. I was talking to a West Berlin Polizeimeister, or police captain, in a wooden shack overlooking the wall, and was being watched through binoculars by a Vopo standing on a raised platform about ten feet on the other side. After a while, I borrowed the policeman’s binoculars, and trained them on the Vopo. He put his glasses down, turned his back, lighted a cigarette with studied nonchalance, and didn’t train the binoculars on me again until I started to leave. (I played this childish game a few more times, usually with much the same result, though not if the Vopos were officers; the officers glowered but didn’t turn away.) “It shouldn’t bother you,” the Polizeimeister said with a smile. “You must remember that everything the Vopos do is calculated to intimidate us, or to try to. They want to give us the feeling that we’re being watched and that we’re helpless to do anything about it.” Later that day, he took me out to a suburban neighborhood on the sector border, where the wall consisted mainly of barbed-wire fencing. On the West Berlin side, workmen were noisily constructing a new housing development. The East Berlin side was seemingly deserted. “We’re being watched, of course,” the Polizeimeister said, and pointed to places on the roofs of four houses across the border where several pieces of slate had been removed. “The Vopos made those observation slits, and they’re probably up there in one of those attics now, looking out. For them, it’s like in war. They’re always taking cover, spying from concealed positions. They like to stay out of sight, and then appear suddenly with binoculars fixed on you. If they’re not up in an attic, they may be over there on the ground, behind the hedges. Some of them are pretty clever at hiding themselves. It takes a while to pick them out. Our men on border duty work a shift of two hours on and one hour off. If you’re on too long at a stretch, you don’t see the Vopos.”

Though the flow of refugees into West Berlin was long ago reduced to a trickle, the East Germans are still strengthening the barriers relentlessly. This past summer, squads of between three hundred and five hundred Vopos could be seen at work along the wall and the zonal border nearly every day. In a great many places, barbed wire was replaced by a concrete wall, rows of tank traps made of old streetcar rails were set up, and more dwellings were sealed or demolished. Seventy concrete pillboxes with observation slits and gun ports were constructed at intervals a short distance behind “the anti-Fascist rampart,” as the East German press sometimes calls the wall. Frogmen of the East German Army strung wire fences in the Spree and other waterways, and squads of Vopos cut down the tall grass and the bushes on the East Berlin shores of rivers and lakes The border guards assigned to the waterways were equipped with new and faster patrol boats. Concurrently, some forty construction workers, guarded by two hundred Vopos, began to build, first in one place and then in another, a second wall about half a block behind the first; this was designed to help Vopos cut down refugees before they could reach the original wall, where West Berlin policemen, photographers, and journalists could witness and record the shooting. Early in August, a machine gun was installed on top of the Brandenburg Gate. According to Richard Crossman, chairman of the British Labour Party, who returned from a visit to East Germany in late August, Ulbricht plans to extend the wall along the entire zonal border, and thus turn West Berlin into “an island completely surrounded by a full-fledged national frontier.” The projected extension will cost well over twice as much as die Mauer, which already represents a considerable investment for a country whose economic situation is as precarious as East Germany’s. On the first anniversary of the erection of the wall, the West Berlin newspaper Berliner Morgenpost reported that a consensus of estimates by engineers and construction contractors placed the cost of the wall and the zonal barrier at about a hundred million West marks, or approximately twenty-five million dollars. That includes the cost of some thirty-eight hundred miles of barbed wire, which is enough, the paper noted, to fence in half of Europe.

Though the flow of refugees into West Berlin was long ago reduced to a trickle, the East Germans are still strengthening the barriers relentlessly. This past summer, squads of between three hundred and five hundred Vopos could be seen at work along the wall and the zonal border nearly every day. In a great many places, barbed wire was replaced by a concrete wall, rows of tank traps made of old streetcar rails were set up, and more dwellings were sealed or demolished. Seventy concrete pillboxes with observation slits and gun ports were constructed at intervals a short distance behind “the anti-Fascist rampart,” as the East German press sometimes calls the wall. Frogmen of the East German Army strung wire fences in the Spree and other waterways, and squads of Vopos cut down the tall grass and the bushes on the East Berlin shores of rivers and lakes The border guards assigned to the waterways were equipped with new and faster patrol boats. Concurrently, some forty construction workers, guarded by two hundred Vopos, began to build, first in one place and then in another, a second wall about half a block behind the first; this was designed to help Vopos cut down refugees before they could reach the original wall, where West Berlin policemen, photographers, and journalists could witness and record the shooting. Early in August, a machine gun was installed on top of the Brandenburg Gate. According to Richard Crossman, chairman of the British Labour Party, who returned from a visit to East Germany in late August, Ulbricht plans to extend the wall along the entire zonal border, and thus turn West Berlin into “an island completely surrounded by a full-fledged national frontier.” The projected extension will cost well over twice as much as die Mauer, which already represents a considerable investment for a country whose economic situation is as precarious as East Germany’s. On the first anniversary of the erection of the wall, the West Berlin newspaper Berliner Morgenpost reported that a consensus of estimates by engineers and construction contractors placed the cost of the wall and the zonal barrier at about a hundred million West marks, or approximately twenty-five million dollars. That includes the cost of some thirty-eight hundred miles of barbed wire, which is enough, the paper noted, to fence in half of Europe.

The continuing expansion of the East German border fortifications has been accompanied by a steady strengthening of the police and Army units assigned to them. At present, the Communist barricades enclosing West Berlin are guarded by three brigades, totalling eighteen thousand men. (The West Berlin side of the border is in the hands of fifteen hundred police.) The Vopos on border duty, according to the Polizeimeister with whom I became acquainted, have changed in character, and not for the better. “Before the wall, we used to have quite a bit of contact with the Vopos,” he said. “I remember one night, on an inspection tour, I stopped at the Moritzplatz station of the U-Bahn—the border cuts right through that station—and there were two of our men and two of their men playing cards across the border. We didn’t usually get that clubby, but in those days a great many of the Vopos were people from Berlin, and we could usually find something to exchange a few words about—sports, personal matters, and such. Of course, they were all youngsters— eighteen or nineteen—and still are, so there’s never been any point in talking politics with them. What do they know about politics? How old were they when the war ended? One? Two? Three? You might mention, for instance, that some friend of yours had just made a trip to the Tyrol on his vacation. They’d say, ‘Sure, capitalists can take vacations.’ And you’d say, ‘He isn’t a capitalist. He’s a locksmith.’ But you couldn’t make them believe you. They might ask about the potato ration, and you’d tell them there wasn’t any ration—you could buy all you wanted. They’d say, ‘Oh, yes, in West Berlin, but in West Germany your people are starving.’ They just wouldn’t believe anything. It was useless.”

The continuing expansion of the East German border fortifications has been accompanied by a steady strengthening of the police and Army units assigned to them. At present, the Communist barricades enclosing West Berlin are guarded by three brigades, totalling eighteen thousand men. (The West Berlin side of the border is in the hands of fifteen hundred police.) The Vopos on border duty, according to the Polizeimeister with whom I became acquainted, have changed in character, and not for the better. “Before the wall, we used to have quite a bit of contact with the Vopos,” he said. “I remember one night, on an inspection tour, I stopped at the Moritzplatz station of the U-Bahn—the border cuts right through that station—and there were two of our men and two of their men playing cards across the border. We didn’t usually get that clubby, but in those days a great many of the Vopos were people from Berlin, and we could usually find something to exchange a few words about—sports, personal matters, and such. Of course, they were all youngsters— eighteen or nineteen—and still are, so there’s never been any point in talking politics with them. What do they know about politics? How old were they when the war ended? One? Two? Three? You might mention, for instance, that some friend of yours had just made a trip to the Tyrol on his vacation. They’d say, ‘Sure, capitalists can take vacations.’ And you’d say, ‘He isn’t a capitalist. He’s a locksmith.’ But you couldn’t make them believe you. They might ask about the potato ration, and you’d tell them there wasn’t any ration—you could buy all you wanted. They’d say, ‘Oh, yes, in West Berlin, but in West Germany your people are starving.’ They just wouldn’t believe anything. It was useless.”

All the same, fraternization led many Vopos to defect, and in order to eliminate it the East Germans began, around the first of this year, to transfer the Berliners on duty at the wall and the zonal border—some two thousand, all told—to other units, and to replace them with young Vopos from rural areas, mainly Saxony. The changeover has been completed, and the boundary is now guarded solely by outlanders, who are referred to by some East Berliners as “the fifth occupying power.” The political indoctrination of these generally rough country boys has been stepped up, and the various units are kept isolated from one another to discourage the exchange of subversive ideas. Each company is assigned to Berlin for only six months, on the average, and a company that loses as many as ten men is replaced immediately. For the most part, the Vopos now on the borders of West Berlin are reliable, sternly disciplined, and tough. At least, they try to look and act tough. One day a while ago, Ernst Lemmer, the Bonn Minister for All-German Affairs, paid a visit to the wall with a small group of West German journalists and made a gesture of greeting to two Vopos standing sentry. He got no response. “You don’t have to look at us so angrily,” he called to them. “Remember, all of us are Germans. And I hope we will all get out of this dilemma by peaceful means.” One of the Vopos laughed; the other spat.

All the same, fraternization led many Vopos to defect, and in order to eliminate it the East Germans began, around the first of this year, to transfer the Berliners on duty at the wall and the zonal border—some two thousand, all told—to other units, and to replace them with young Vopos from rural areas, mainly Saxony. The changeover has been completed, and the boundary is now guarded solely by outlanders, who are referred to by some East Berliners as “the fifth occupying power.” The political indoctrination of these generally rough country boys has been stepped up, and the various units are kept isolated from one another to discourage the exchange of subversive ideas. Each company is assigned to Berlin for only six months, on the average, and a company that loses as many as ten men is replaced immediately. For the most part, the Vopos now on the borders of West Berlin are reliable, sternly disciplined, and tough. At least, they try to look and act tough. One day a while ago, Ernst Lemmer, the Bonn Minister for All-German Affairs, paid a visit to the wall with a small group of West German journalists and made a gesture of greeting to two Vopos standing sentry. He got no response. “You don’t have to look at us so angrily,” he called to them. “Remember, all of us are Germans. And I hope we will all get out of this dilemma by peaceful means.” One of the Vopos laughed; the other spat.

8-1-1963, DEC 6 1969, DEC 10 1969

A sentry fixes his binoculars on activity across the Berlin Wall

The wall of iron, wire and stone went up in that heated summer of 1961.

Credit: Flip Schulke

archiveblog

According to a knowledgeable member of the United States Mission in Berlin, there used to be a number of places on the border where one could arrange an escape by bribing the Vopos, but pay-as-you-leave exits now seem to be a thing of the past. Today, a person who tries to buy his way across the border runs a grave risk, as the East German press likes to point out every so often in stories about Vopos who have covered themselves with glory by spurning bribes. Not long ago, for example, Neues Deutschland, the principal East German newspaper, reported that one night four Vopos on guard duty at an outlying section of the wall were approached by two young women, who offered them four thousand marks to let them and their families through to West Berlin. The Vopos agreed, took the money, and set the time and place for the planned escape. Then they reported the details to the Staats Sicherheitsdienst, or S.S.D—the State Security Service—and when the young women and eight of their relatives turned up as planned, before dawn the following day, agents of the S.S.D. put them under arrest. Each of the Vopos was decorated with a medal and given a reward of a hundred marks. Rewards are also given to children for informing against East Germans who they fancy are trying to escape. Recently, the East German newspaper Das Volk published a long article praising members of the Young Pioneers (the Communist organization for children between ten and fourteen) who had “assisted the police in their task of defending the rampart against aggression.” Heidi Mallowitz was congratulated because “as soon as she noticed a stranger walking near the border, she reported to her father, and he alerted the police, who arrested the criminal border violator.” As a reward, Heidi received a track suit. Another Young Pioneer, Horst Bratke, detected a stranger in the fog and immediately called the border guards, who arrested the man. Horst received a sports shirt and a soccer ball.

In the course of “defending the rampart,” the Vopos have so far killed at least fifty of their countrymen—some of them children. That is the number of killings at the border that have been witnessed by the West Berlin police; the actual number, in the opinion of Ernst Lemmer, exceeds a hundred. The fiftieth known victim was an eighteen-year-old East German named Peter Fechter. Shortly after noon on August 16, 1962, he was shot in the stomach and the back as he attempted to scale the wall two blocks from the celebrated Checkpoint Charlie, on Friedrichstrasse; he was left unattended for more than an hour, and bled to death. As he lay dying, hundreds of West Berliners assembled close enough to their side of the wall to hear the youth’s screams for help; newspaper reporters and photographers appeared; American military police arrived on the scene but withdrew to Checkpoint Charlie when Vopos threw tear-gas bombs into the crowds; and an American Army helicopter circled over the area. The killing of Peter Fechter set off five days of riotous demonstrations by West Berliners, many of whom were bitterly resentful because no Americans went to the aid of the wounded refugee. Barbarous as the murder of Peter Fechter was, it was no more so than the other killings that the Vopos have been responsible for since August 24, 1961—eleven days after the wall came into existence—when they shot their first refugee, a twenty-five-year-old East Berliner who was trying to reach West Germany by swimming the Humboldt Harbor Canal. Not a week has since passed that they have not killed or wounded another man, woman, or child.

In the course of “defending the rampart,” the Vopos have so far killed at least fifty of their countrymen—some of them children. That is the number of killings at the border that have been witnessed by the West Berlin police; the actual number, in the opinion of Ernst Lemmer, exceeds a hundred. The fiftieth known victim was an eighteen-year-old East German named Peter Fechter. Shortly after noon on August 16, 1962, he was shot in the stomach and the back as he attempted to scale the wall two blocks from the celebrated Checkpoint Charlie, on Friedrichstrasse; he was left unattended for more than an hour, and bled to death. As he lay dying, hundreds of West Berliners assembled close enough to their side of the wall to hear the youth’s screams for help; newspaper reporters and photographers appeared; American military police arrived on the scene but withdrew to Checkpoint Charlie when Vopos threw tear-gas bombs into the crowds; and an American Army helicopter circled over the area. The killing of Peter Fechter set off five days of riotous demonstrations by West Berliners, many of whom were bitterly resentful because no Americans went to the aid of the wounded refugee. Barbarous as the murder of Peter Fechter was, it was no more so than the other killings that the Vopos have been responsible for since August 24, 1961—eleven days after the wall came into existence—when they shot their first refugee, a twenty-five-year-old East Berliner who was trying to reach West Germany by swimming the Humboldt Harbor Canal. Not a week has since passed that they have not killed or wounded another man, woman, or child.

“In Berlin and at the zonal border, Germans shoot at Germans,” the Hamburg newspaper Bild-Zeitung observed after one of the recent killings at the wall. “What are we doing? We take notice and are shocked for a moment. Then we put the newspaper aside—that’s it. What is the matter with Germany in 1962? It is a sick Germany. A Germany which is not indignant about injustice and which is not visibly shocked is a shaking Germany.” One expression of indignation, less fleeting than a newspaper story, is the modest memorial erected by anonymous West Berliners to an unknown refugee, who was killed while attempting to swim the Spree. At about five-thirty one evening, I paid a visit to the memorial, which overlooks the river at the place where the slaying occurred. It had begun to drizzle. Only three people were walking along the riverbank, and there was no activity on the river, which was glassy and looked leaden. On the East Berlin side—some hundred and fifty yards away—the warehouses and other buildings lining the bank had apparently been closed for the day, though there was no way of telling, since all of the doors and windows facing the river had been bricked up. The gaps between the structures had been closed to form the familiar, desolate wall. Somewhere along that bank late one afternoon, a man in his early twenties stripped to the waist, tied a small leather pouch around his neck, slipped into the water, and struck out for the western shore He had reached the middle of the river when the Vopos spotted him and opened fire, first with rifles and then with submachine guns. While West Berliners looked on in horror, the swimmer was struck in the head, and sank. His body was recovered by the West Berlin police. His memorial, set in a small flower bed, consists of a cross made of rough wood painted black; attached to the crosspiece is a festoon of barbed wire. Beneath this is a framed photograph of the unknown refugee lying in a coffin and, at the bottom of the photograph, the hand-lettered words “Du könntest unser Bruder sein” (“You might have been our brother”).

“In Berlin and at the zonal border, Germans shoot at Germans,” the Hamburg newspaper Bild-Zeitung observed after one of the recent killings at the wall. “What are we doing? We take notice and are shocked for a moment. Then we put the newspaper aside—that’s it. What is the matter with Germany in 1962? It is a sick Germany. A Germany which is not indignant about injustice and which is not visibly shocked is a shaking Germany.” One expression of indignation, less fleeting than a newspaper story, is the modest memorial erected by anonymous West Berliners to an unknown refugee, who was killed while attempting to swim the Spree. At about five-thirty one evening, I paid a visit to the memorial, which overlooks the river at the place where the slaying occurred. It had begun to drizzle. Only three people were walking along the riverbank, and there was no activity on the river, which was glassy and looked leaden. On the East Berlin side—some hundred and fifty yards away—the warehouses and other buildings lining the bank had apparently been closed for the day, though there was no way of telling, since all of the doors and windows facing the river had been bricked up. The gaps between the structures had been closed to form the familiar, desolate wall. Somewhere along that bank late one afternoon, a man in his early twenties stripped to the waist, tied a small leather pouch around his neck, slipped into the water, and struck out for the western shore He had reached the middle of the river when the Vopos spotted him and opened fire, first with rifles and then with submachine guns. While West Berliners looked on in horror, the swimmer was struck in the head, and sank. His body was recovered by the West Berlin police. His memorial, set in a small flower bed, consists of a cross made of rough wood painted black; attached to the crosspiece is a festoon of barbed wire. Beneath this is a framed photograph of the unknown refugee lying in a coffin and, at the bottom of the photograph, the hand-lettered words “Du könntest unser Bruder sein” (“You might have been our brother”).